Enchanted Pilgrimage

by Clifford D. Simak

p. 1975

Thursday, April 30, 2015

Doubletake

Doubletake

by Rob Thurman

p. 2012

by Rob Thurman

p. 2012

Family reunions are the name of the

game in Rob Thurman’s 2012 contribution to the Cal Leandros mythology, as each

of the three main characters deal with blasts from the past intent on upsetting

their already tumultuous lives. A chain of events brings these shady relatives

into Cal and Niko’s orbit and leads the brothers to question whether they can

trust someone new (hint: no.) while it leads me to question whether Thurman is capable of something new. (hint:

yeahhhhhno.)

It’s Goodfellow’s kin that sets off

the series of reunions as every puck in existence gathers in New York City for

‘The Panic,’ their thousand-year reunion meant to tally their number and

participate in a lottery to decide who must reproduce to keep the population

going for another thousand years. Robin has opted to hire Cal and Niko as

bouncers to keep the situation under control and the results are predictably

awkward but undeniably hilarious. It’s important to remember that all the pucks

look nearly identical, so even though ‘their’ puck is the only non-participant,

due to his ongoing experimentation with monogamy, it’s impossible to escape the

sight of Robin fornicating with everything in sight, including variations of

himself. Cal and Niko’s front row seats to the orgy of the century were so

hilariously outrageous that for a few chapters I almost wondered if perhaps Thurman was attempting to do a humorous

filler novel for once. It would have been the perfect place for it—coming directly

after Cal’s emotional stint with amnesia, which ended with him wiping out the

remnants of his monster-reject family, the last vestiges of his Auphe family

tree.

Or so he thought. Naturally, there

was one ‘brother’ that Cal missed, and he becomes the central antagonist of Doubletake, and definitely future

installments too, considering he’s still kicking it above ground by novel’s end.

This monstrosity was one of the last failed experiments of the Auphe, incapable

of facilitating their evil plan but still capable of creating gates and very

much in possession of the Auphe’s twisted sensibilities. Once he escaped from

his captive adolescence, Cal’s twisted ‘brother’ educated himself, taught

himself to fight, adopted the name Grimm and relegated himself to the fringes, waiting

for his chance at revenge against his race. When Cal robs him of this chance,

Grimm switches his sights to Cal, and reveals himself for the first time in Doubletake with a new plan for creating his own destructive race—and he wants Cal’s

help to get things started.

Disappointingly, it’s more of the

same with Grimm—the slimy, all-powerful villain who talks too much and is evil

for evil’s sake. This of course means lots of diabolical monologuing and heavy

angst. It also means another villain whose intentions are predictable and not

at all relatable. It also means, I am

cheated out of my potentially humorous filler novel, but that rude awakening preceded Grimm’s entrance in the form of Niko’s

shady relative—his erstwhile father, Kalakos, a gypsy bounty hunter of sorts

who is in town hunting down the Vayash Clan’s latest escaped responsibility, Janus.

Janus is a monster made of metal and fire and it is intent on tracking down and

killing every member of the Vayash Clan (even, according to Kalakos, exiled

members like Cal and Niko who want nothing to do with the clan). The brothers

reject Niko’s father’s attempt to reach out, but are forced to rely on him when

Cal is gravely wounded by Janus.

Kalakos was definitely the thread I

was most interested in, of the three family reunions. Where Cal’s interactions

with Grimm brought nothing new to the table and Goodfellow’s kin brought only

laughs, it is Niko’s reaction to his father that brings the most questions. Cal

is loyal to a fault; we know he trusts no one and will choose any avenue that

most thoroughly protects his brother, so he leaves the decision to Niko on

whether or not Kalakos should be allowed in the picture. As Niko’s estranged

father accompanies the boys on their two-way Janus hunt, the latter are forced

to ask themselves whether they can forgive Kalakos after abandoning them all

their lives.

I’ll admit, I wondered if it could

work out. Cal and Niko had accepted others into their circle before. Promise

and Rafferty are always on the guest list and of course one doesn’t get more ‘inner

circle’ than Goodfellow, who the brothers trust implicitly. I allowed myself to

hope that perhaps Kalakos could earn

forgiveness and be another capable character for the brothers to rely on, maybe

a rogue who pops his head in every now and then to offer support...

... Oh, how foolish that was.

Sure enough, Kalakos not only

proves what Cal and Niko knew all along—that he is not to be trusted—but he

also completely loses the cool, rational demeanor he’d held for the entire book

and spontaneously starts monologuing about how eeeeevil he is. It’s almost like

Thurman’s villains cannot help themselves. They just have to prove their evil worth by not shutting the fuck up.

It’s disappointing because there

are dozens of ways this could have gone and I imagined most of them. Kalakos

could have been on the level and become a new ally, he could have have been on

the level and died tragically, the brothers could have not trusted him then

regretted it when he turned out to be legit, or they could have allowed

themselves to forgive only to be let down. Literally any option that allows

some combination of these characters to grow emotionally would have been more

interesting than what we got. But instead, Kalakos was a bastard all along,

surprising precisely nobody. But we’re going to pretend like nobody saw it

coming so he can get his villain on in the final act. Yawn.

I’m being a little hard on Doubletake. I liked it like I liked any

of the other books in this series, I’m just hoping for a new take on things

soon, a promise of emotional growth, and maybe some new characters for the

inner circle. If anything, Doubletake

actually took away one of the inner

circle in the only surprising twist in the book, which I have avoided mentioning

until now because it seems about as relevant in this review as it does in

the actual book. What I’m referring to is the revelation that George—Cal’s old

psychic paramour—the good-hearted girl next door who exiled herself when Cal

refused to let her in—the girl whom we haven’t heard from or spoken to in at

least 4 books—was brutally murdered by Grimm ‘off screen,’ so to speak. The

truth isn’t revealed to our intrepid heroes this time around, making its

inclusion here seem kind of random, but in a good way, like a bullet that has

been fired but has not yet found its mark. When that bullet hits, I expect all

hell to break loose. I only hope that we get proper chance to say goodbye to

Georgie when that happens, because she deserves better than the ending she

apparently got.

The Cloud Atlas

The Cloud Atlas

by Liam Callanan

p. 2004

by Liam Callanan

p. 2004

In 2013, I watched a movie called Cloud Atlas and was thoroughly perplexed

but entranced enough by it to read the book, which I eventually popped onto

Amazon and bought some months later. I didn’t get around to reading it until

early this year, thoroughly excited to finally get a new perspective on this

complicated story... only to discover I’d purchased the wrong book.

That’s right. Who knew that Cloud Atlas was a completely different

book than THE Cloud Atlas?

Well, now at least the two of us

know.

Cloud

Atlas, by David Mitchell, wrote a book published in 2004 and, though it was

considered unfilmable, it was eventually the inspiration for the 2012 film. The

book I bought on accident, THE Cloud

Atlas, was also published in 2004

and written by Liam Callanan and other than the name, has absolutely nothing in

common with the film, which is why it’s a bit ridiculous that it took me almost

50 pages to figure out... I honestly thought that maybe there were other

stories in the book that they didn’t write into the script and continued to

allow myself to think this until the ‘unheard story’ went on for just too many

pages to be a ‘cut scene.’

Putting aside my disappointment, I

decided to give the novel a chance—it wasn’t too bad, had an interesting

premise, and I was already 50 pages in, after all.

The

Cloud Atlas is something of a coming-of-age tale set in Alaska during World

War II and focuses on a young bomb disposal officer, Louis Belk, and his secret

assignment in the remote northern territory seeking out ‘balloon bombs’ released

by the Japanese and scattered all about the western half of mainland United

States. Since I still thought—for the first quarter at least—that I was reading

a book with fantasy elements, I assumed the balloon bombs were the result of

fiction, a far-fetched and strange idea given life on the page. Once I realized

I was reading the wrong book, I looked it up and apparently it’s all based on

real—albeit highly unpublicized—maneuvers by the Japanese army in 1945. Theyreally did release 9000 balloons with incendiary devices and they really did

land all over the US and parts of Mexico and Canada, a few even extending as

far as Michigan.

Seeing as this ploy was, on the

whole, largely ineffective, the project was abandoned before the end of the

war, and only 300 or so balloons were reported, but the remains of several are

still being found to this day. The balloons only caused fatalities in one

single incident, and sadly it was all civilians—a pregnant woman and five

children who discovered the balloon weeks after it had landed were all killed

when it exploded—but considering the existence of the horrendous Unit 731, the potential of the balloons

destructiveness still make for an intriguing story. The threat of forest fires

from the incendiary bombs is upsetting enough, but the mere idea of biological

warfare enacted upon a civilian population is terrifying; I can easily see why Callanan

chose it as the subject of his novel.

As for the novel itself, I wasn’t

entirely charmed by it. Though I liked the characters well enough, I thought it

could be a bit boring as well. Though it presents itself by all accounts as a

classic coming-of-age story of a young man in World War II, I don’t really feel

like the protagonist learned or grew much from his experience besides, perhaps,

a lasting appreciation for the region of Alaska in which he was stationed and

the spirituality of its native people, the Yu’pik.

There is a love quadrangle that

doesn’t do this book any favors. I might have overlooked it had one less male

suitor been involved but the presence of all four people in the relationship

felt out of place and wholly unnecessary in such a richly historical tale of

intrigue.

Callanan’s writing style is pretty

enjoyable; there were definitely a few parts that caused me to laugh aloud, but

they also immediately struck me as borrowing heavily from Catch-22, especially in Belk’s interaction with his larger-than-life

commanding officer, Captain Gurley, who is deeply obsessed with discovering and

stopping the threat of the Japanese balloons.

I’m not sorry I read this book,

though I do wish I’d purchased the right one last year. It ended up being a

happy little accident that may not have introduced me to my new favorite book

but did teach me some facts about World War II that I had never even heard of

prior to this. The Cloud Atlas is

certainly a thoughtful and well-composed take on a little-known piece of

history. Anyone interested in historical fiction or World War II should

certainly give this book a chance.

Bag of Bones

Bag of Bones

by Stephen King

p. 1998

by Stephen King

p. 1998

Michael Noonan is haunted.

As the tragic lead protagonist in

Stephen King’s 1998 novel, widower Mike Noonan finds him at the center of

several dangerous and emotional plots when he retreats to his summer home in an

attempt to move on with his life.

Bag

of Bones is only my second King novel, and it leans closer to the genre he

is best known for: horror and suspense. Indeed, the sprawling, multi-layered

story is in turns mysterious, disturbing, tragic and dark. It wasn’t as long as

my first King novel, but then few books are. It does, however, share some

themes that may be King trademarks, not the least of which is having a widowed

male protagonist who could be a stand-in for King himself. In this case, it is

a little more transparent: Mike Noonan is a popular author who finds himself

unable to write a single word since the unexpected death of his wife, Johanna,

some years earlier.

In an attempt to make sense of the

strange nightmares he keeps having, Mike decides to go to the location that

keeps recurring in them: his vacation house on Dark Score Lake in small town

Maine, nicknamed Sara Laughs for its notorious history with an old blues

singer, Sara Tidwell. On his first day back, Mike’s life becomes intertwined

with that of a young mother, Mattie Devore, and her 3-year-old daughter, Kyra.

Reminded of his own childless marriage and attracted to the alluring

Mattie—herself a young, tragic widow—Mike becomes embroiled in an ensuing

custody battle for Kyra, led by the girl’s paternal grandfather, a multi-millionaire

tycoon who is determined to always get what he wants.

Bag

of Bones is a long book but it needs to be; there are plenty of plot

threads, each with its own respective history, that are thoroughly explored

before all coming together at the climax of the story. This is not a gory

horror novel, as the suspense relies mainly on ghostly encounters and

nightmarish secrets, but there are some starkly disturbing elements, especially

that of the fate of Sara Tidwell and her kin and the ultimate fate of Mattie

Devore, the latter of which took me especially by surprise. I did not expect

King to kill his female lead so violently (after mercifully letting the main

couple live in The Stand), but I

guess I should have seen it coming. Mattie and Kyra were just so disgustingly precious that they couldn’t possibly be

allowed to endure past novel’s end. I mean, where would the story be in that?

Though there were no female-to-female

relationships in Bag of Bones

(outside of the mother-daughter relationship), the novel is possessed and led

by the actions of many interesting female characters: Mattie and Kyra, who

provide the immediate action for the plot; Jo, who—though long deceased—haunts

Sara Laughs and guides Mike on his spiritual journey to the truth; Sara

Tidwell, whose fate began a curse culminating in the final showdown of the

present, and Sara Laughs—the house who is herself like a living, breathing

character. Even Max Devore’s spindly, prickly assistant, Rogette Whitmore, is a

dynamic if villainous character who brings life to the novel, even if she is,

at times, a bit over the top. I only wish that Mattie didn’t present as such a

disposable character. Arguably the female lead, she should have presented as a

stronger character, but she relied heavily on others to save her, and felt like

more of a temptation and a complication for Mike than an individual. I have to

admit I was a little grossed out by his fantasizing about this girl half his

age, and it gets weirder when you realize that Mattie was really only a means

of Mike getting what he always wanted (his own child), before being

conveniently disposed of. Perhaps that last part is an oversimplification, perhaps

not. The story is about the haunting of Mike Noonan, after all, everyone else

is necessarily secondary to the story.

I didn’t enjoy this story as much

as The Stand; even though it was

somewhat shorter, I feel it dragged on at times, or took too long to get to the

action, but these were minor points of contention for me. For the most part, I

like slow-boiling plots and character-driven stories, as long as they are

presented with a modicum of poetry and poise, and Stephen King is wonderful at

demonstrating those. It mostly comes down to my genre preferences: The Stand is a post-apocalyptic story,

one of my favorite genres, while Bag of

Bones, a horror novel, is a genre I’m less likely to be invested in. The

fact is, horror stories, to someone as pragmatic as I typically am, require

much more suspension of disbelief. If Bag

of Bones had culminated in a psychological and wholly realistic finale as

opposed to a mystical one, I might have a different opinion altogether.

Saturday, January 31, 2015

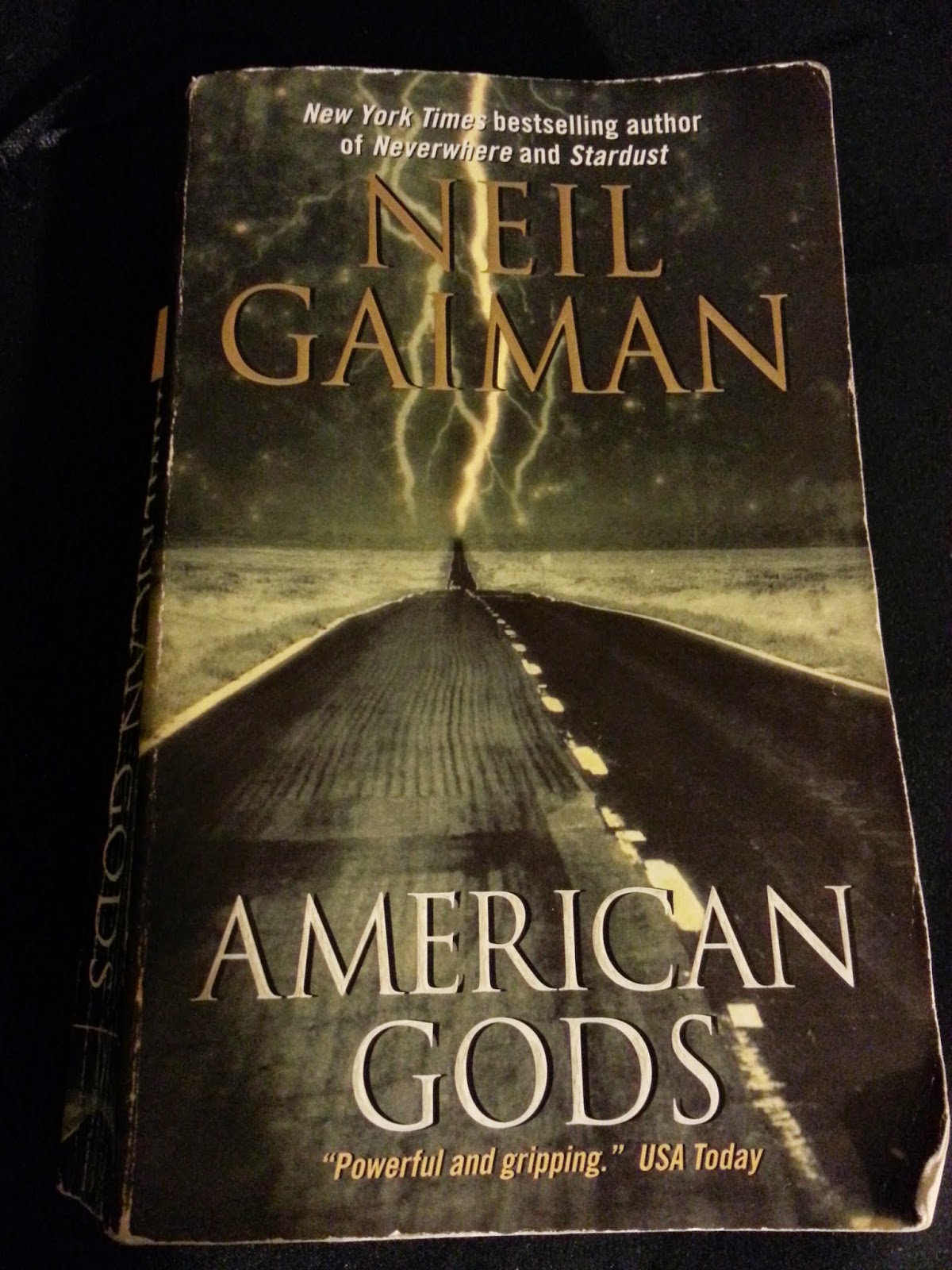

American Gods

American Gods

by Neil Gaiman

p. 2001

by Neil Gaiman

p. 2001

American

Gods is a book I’d been meaning to read for quite some time, penned by Neil

Gaiman, whose specialty—I’ve gathered, now that I’m three books in—is taking

old school fantasy and mythology and transplanting it into a contemporary

setting. With Neverwhere, it was

magic and mysticism. With Good Omens

it was angels and demons and Horsemen of the Apocalypse. With American Gods, it’s the gods and myths

of various cultures. In all three, there is a recurring theme of these legends

struggling to fit into a world that has no place for them anymore.

American

Gods is so thick and layered that it would be impossible to cover every

detail in a few paragraphs. The gist of the story is that a young man named

Shadow is released from jail following the death of his wife and finds himself

falling in with a mysterious conman named Mr. Wednesday and his strange and

quirky associates. Wednesday employs Shadow as a bodyguard and reveals himself,

in time, to be the modern American reincarnation of Odin, the Norse god. In this

story, the power of the gods is determined by how strongly people believe in

them. Some, like Wednesday and his colleagues, are Americanized incarnations of

the old gods, brought over from other continents in the old days, and their

power has diminished as they get farther away from their origins. Others are

new American gods, created and molded by a society whose values have moved on

to other things—such as technology and drugs. Both factions are in a sort of

cold war which Wednesday believes to be heating up; he has dedicated himself to

rallying the troops accordingly for the coming battle, and Shadow finds himself

caught in the middle of it all.

That only begins to describe

everything that is going on in this heady book. There are tons of vignettes and

side stories, some depicting various gods and their histories traveling to the

Americas, some about Shadow’s dead wife, resurrected with a magic trick and

dedicated to protecting her husband in exchange for a return to the living, and

the longest subplot: Shadow’s time hidden away by Wednesday in a small town

called Lakeside, where he bonds with the locals. It seems strange that in a book

about gods and goddesses and mysterious men in black and the undead that one of

the most compelling parts would be Shadow’s attempts at domestication in small

town USA and yet, when Shadow is inevitably outed and exiled from the modest

life he has created for himself, it is somehow the most heartbreaking part of

the story—even more than Wednesday’s ‘death’ just prior.

I was a little disappointed by American Gods, perhaps because the hype

exceeded the depth of the material. Don’t get me wrong, I still enjoyed the

story, but I also found it a little boring at times, and I think the climax of

the book was a bit of a letdown. What prompted me to finally plunge into

Gaiman’s book was hearing that it was soon to be developed into a miniseries

for cable. Upon reading it, I can see now that that is really the only way it

can be translated to screen. A movie wouldn’t begin to cover it all, not even

if it were split up into a trilogy, because (as we learned with The Hobbit) there is no logical stopping

point for each film. In this golden age of matured television programming, a

miniseries would be best, and then only for cable, where the subject matter can

be explored on American screens without the restraint of network censorship.

I’ll look forward to seeing how the material plays out and may have to check

out Gaiman’s other stories set in this same universe.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)