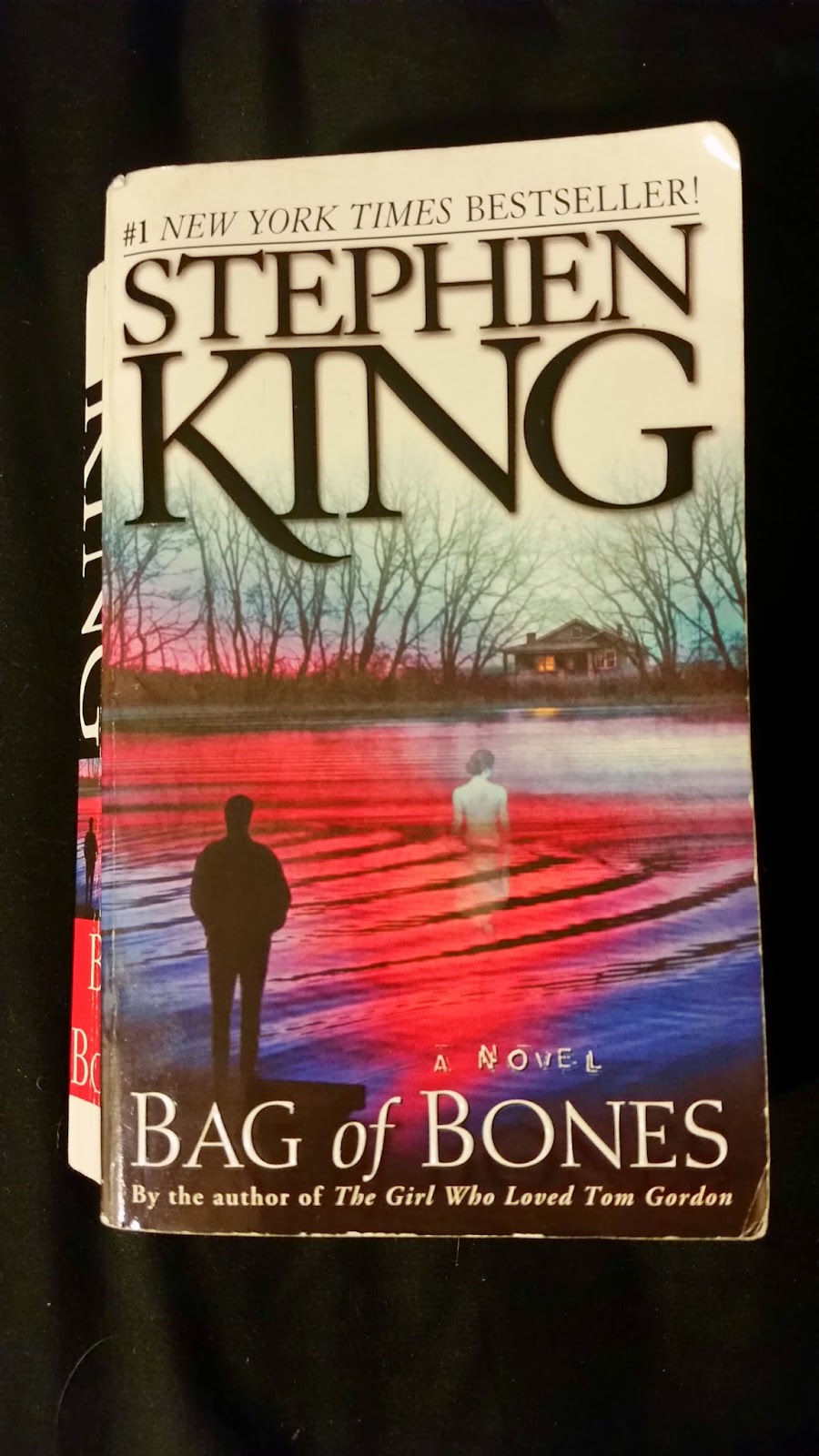

by Stephen King

p. 1998

Michael Noonan is haunted.

As the tragic lead protagonist in

Stephen King’s 1998 novel, widower Mike Noonan finds him at the center of

several dangerous and emotional plots when he retreats to his summer home in an

attempt to move on with his life.

Bag

of Bones is only my second King novel, and it leans closer to the genre he

is best known for: horror and suspense. Indeed, the sprawling, multi-layered

story is in turns mysterious, disturbing, tragic and dark. It wasn’t as long as

my first King novel, but then few books are. It does, however, share some

themes that may be King trademarks, not the least of which is having a widowed

male protagonist who could be a stand-in for King himself. In this case, it is

a little more transparent: Mike Noonan is a popular author who finds himself

unable to write a single word since the unexpected death of his wife, Johanna,

some years earlier.

In an attempt to make sense of the

strange nightmares he keeps having, Mike decides to go to the location that

keeps recurring in them: his vacation house on Dark Score Lake in small town

Maine, nicknamed Sara Laughs for its notorious history with an old blues

singer, Sara Tidwell. On his first day back, Mike’s life becomes intertwined

with that of a young mother, Mattie Devore, and her 3-year-old daughter, Kyra.

Reminded of his own childless marriage and attracted to the alluring

Mattie—herself a young, tragic widow—Mike becomes embroiled in an ensuing

custody battle for Kyra, led by the girl’s paternal grandfather, a multi-millionaire

tycoon who is determined to always get what he wants.

Bag

of Bones is a long book but it needs to be; there are plenty of plot

threads, each with its own respective history, that are thoroughly explored

before all coming together at the climax of the story. This is not a gory

horror novel, as the suspense relies mainly on ghostly encounters and

nightmarish secrets, but there are some starkly disturbing elements, especially

that of the fate of Sara Tidwell and her kin and the ultimate fate of Mattie

Devore, the latter of which took me especially by surprise. I did not expect

King to kill his female lead so violently (after mercifully letting the main

couple live in The Stand), but I

guess I should have seen it coming. Mattie and Kyra were just so disgustingly precious that they couldn’t possibly be

allowed to endure past novel’s end. I mean, where would the story be in that?

Though there were no female-to-female

relationships in Bag of Bones

(outside of the mother-daughter relationship), the novel is possessed and led

by the actions of many interesting female characters: Mattie and Kyra, who

provide the immediate action for the plot; Jo, who—though long deceased—haunts

Sara Laughs and guides Mike on his spiritual journey to the truth; Sara

Tidwell, whose fate began a curse culminating in the final showdown of the

present, and Sara Laughs—the house who is herself like a living, breathing

character. Even Max Devore’s spindly, prickly assistant, Rogette Whitmore, is a

dynamic if villainous character who brings life to the novel, even if she is,

at times, a bit over the top. I only wish that Mattie didn’t present as such a

disposable character. Arguably the female lead, she should have presented as a

stronger character, but she relied heavily on others to save her, and felt like

more of a temptation and a complication for Mike than an individual. I have to

admit I was a little grossed out by his fantasizing about this girl half his

age, and it gets weirder when you realize that Mattie was really only a means

of Mike getting what he always wanted (his own child), before being

conveniently disposed of. Perhaps that last part is an oversimplification, perhaps

not. The story is about the haunting of Mike Noonan, after all, everyone else

is necessarily secondary to the story.

I didn’t enjoy this story as much

as The Stand; even though it was

somewhat shorter, I feel it dragged on at times, or took too long to get to the

action, but these were minor points of contention for me. For the most part, I

like slow-boiling plots and character-driven stories, as long as they are

presented with a modicum of poetry and poise, and Stephen King is wonderful at

demonstrating those. It mostly comes down to my genre preferences: The Stand is a post-apocalyptic story,

one of my favorite genres, while Bag of

Bones, a horror novel, is a genre I’m less likely to be invested in. The

fact is, horror stories, to someone as pragmatic as I typically am, require

much more suspension of disbelief. If Bag

of Bones had culminated in a psychological and wholly realistic finale as

opposed to a mystical one, I might have a different opinion altogether.